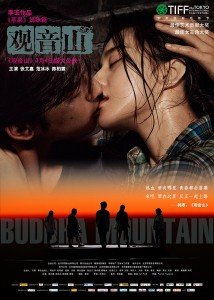

DVD Review: “Buddha Mountain / 观音山” (2010 / China) by Li Yu (李玉)4 min read

Reading Time: 4 minutesSwaying to the heartbeat of pub music, Nan Xing transforms herself into her alter ego in the beginning sequence of the film”“ a nocturnal creature of the night, a sensuous siren singing her hearts out till the wee hours of the night.

Interestingly, the opening scene ends with Nan Xing shutting the door behind her as she exits her apartment, revealing a picture of James Dean hanging on the back of the door as it gently closes ““ a likely tribute to “Rebel Without a Cause” (1955) and an echo of the angst of one’s teenage years ““ serving as a prelude to the troubled nature of the rest of the film.

As Nan Xing, actress Fan Bingbing is the driving force that propels the story forward, supported by her two best friends Ding Bo (played by Chinese actor Chen Bo-ling) and Fei Zhao. They are the three musketeers, the dispirited warriors riding against the common tide of abdolescence, struggling with the balancing act of relentless freedom and helpless financial insecurity.

A chance encounter brought them face to face with a mum (played by Sylvia Chang) who has previously lost her son in a car accident.

With three teenagers entangled with estranged parents (Nan Xing’s mum is stuck in a relationship with a drunkard for a husband while Ding Bo’s father has stayed away from his wife’s death bed), a stark contrast is inadvertently made between one who clings on to her loved one and three who have chosen to disengage from their families, thereby exposing the widening gap between parents and their children in contemporary society.

In the absence of parental love, it’s not uncommon for teenagers to secure a surrogate love for themselves, often in the form of partners of similar age, in this instance between that of Nan Xing and Ding Bo – blurring the line between puppy love and true love. As relationships become more complex due to smaller family units and dysfunctional families in recent years, “Buddha Mountain” seems to pose the question of where the fault lies.

In essence, “Buddha Mountain” is a film that poses more questions than it answers.

Memory is a filmic device brought up time and time again in the film. Is memory a boon or a bane? If it is a bane, why are memories of a mum’s dead son sustenance that keeps her alive? If it is a boon, why are the same memories of her deceased son such a great cause of grief that ceaselessly assaults her with great bouts of melancholiness at unexpected moments? Why is her son’s lover unable to forget her love for her son? And why did memories of the three teenagers’ parents’ pasts haunt them?

Depressing in the beginning, the film seeks to address some questions it has raised by taking a positive turn by reflecting on forgiveness and redemption, leveraging substantially on Buddhist teachings towards the second half of the film, with mild discussions on the adverse effects of liquor, an investigative approach on forgiving the misgivings of one’s parents and more significantly, on spiritual awakening when the three teenagers and the lonely mum got together to rebuild a Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy) temple which has been destroyed in a 2008 earthquake.

Concepts of Buddhism are heavily emphasised as the three teenagers enjoy the in-your-face breeze as they hitched train rides through the countryside (emphasising living in the present moment), the depressed mum ruminating on her life of losing her husband and son (reflective of the fleeting and transient moments of life) and the eventual psychological release of their emotional troubles (exemplifying the practice of letting go).

Peppered throughout the film are snippets of our basic kind nature as the three teenagers tried their best to cheer up the sad mum who has previously attempted suicide, returning whatever cash they have owed her and bonding together as a family.

It is fate that draws dispirited people together but it is love that enables them to fill up the needs of others without any expectation of reciprocation. Indeed, one of the most beautiful aspects of life is that it compensates and revives “and this film reveals this core essence.

“Buddha Mountain” brings to mind one’s golden years when life seems bright, freedom is boundless and possibilities are unlimited. It also brings to light the restrictive constraints and fear that youths experience as they are torn in all directions at the various crossroads of life.

What would you do if you know that one choice you choose will mean a sacrifice of another? Will you still make it?

Afloat on the oceanic stream of the samsaric world, we will eventually come to a realisation that we will need one another to keep each of us on the raft of compassion.

And only together as one body will we swim towards the shore of nirvana.